19Oct2023

“Back in the day,” Sheena Iyengar told the audience at the 2023 NBF VIP Session, “the average individual got married to somebody who lived or worked within a 4-block radius of them. Today, you have over 6,000 different dating apps around the globe for you to find your ‘perfect soulmate.’” And while this may sound like a good thing, as Sheena continued her talk, it became clear that this proliferation of choices has had and continues to have a crippling effect on us.

But the problem gets compounded by just how much information we have access to—which we also must choose from to help us make our decisions.

“It is estimated that the average amount of information confronting the modern-day individual is the equivalent of reading about 174 newspapers.”

Put quite simply, the average person must make about 35,000 decisions in a given week. That number goes up the more companies expand the number of products they offer, the more the internet allows us to quickly communicate with others around the world, and we have access to more information to “help” us make decisions than we ever have before.

The problem of proliferating choices negatively affects not only each person but also companies who rely on customers being able to continue making the choice to buy their products—as well as retailers who need to make decisions about how many brands and varieties within brands to carry.

Sheena’s talk addressed 2 main objectives. First, she discussed 3 reasons why more choices are actually less helpful for both customers and companies. And second, she provided a 4-step process to help make decisions easier—which can be modeled both by individuals and by companies. The result is the embodiment of the old adage less is more. Because when it comes to choices, it turns out that adage is actually more of an immutable law of good business.

Why Choice Overload Affects Us

Around the year 2000, Sheena and her colleagues launched the now famous “Jam Study”. They attempted to test how the number of choices of jam at a grocery store affected how many people actually purchased one. When 24 kinds of jam were offered, only 3% of people bought a jar. But when only 6 were displayed, 30% of the people bought a jar.

Sheena was asked by Vanguard to look at people’s investment choices, and the findings weren’t much different than the Jam Study. “I was given 1 million records of individuals across about 650 different companies in the US and Canada…And what we found was that in the plans that offered more choices, participation rates were lower. The highest participation rates were when you had about a handful of options.” And this is still true today.

Lastly, Sheena gave the example of anxiety medications. When people were given 10 choices of different medications, they reported more side effects of the one they chose. Interestingly, everyone was given a placebo.

So, what does this mean? Sheena advised the audience at the Nordic Business Forum: “The more choices people have, the more likely they are to delay or procrastinate. The more choices people have, the more likely they are to choose sub-optimally. The more choices people have, the less satisfied they are with their choices.” But why is this? There are 3 reasons why more choices make choosing more difficult for us.

Our Brains Are Limited

In 1956, psychologist George Miller coined the theory that humans likely can’t retain more than 7 (plus or minus 2) pieces of information in their head at one time. So, if I’m in the store, trying to decide between—say—24 different kinds of jams, but I’m only able to keep track of 5 to 9 of them in my head—it’s easy to see why I’d be more likely to become overwhelmed and walk away. To make a choice among alternatives, I need to be able to keep track of all the alternatives. Once I’m unable to do that, it becomes more of a guess than anything—with all the post-hoc rationalization that might come with it (hence the side effects from placebos anxiety medication!)

Sheena goes on to say that modern studies using fMRI suggest that the number we once thought to be 7, plus or minus 2, is actually more like 3 to 5. So, we end up having much less of an ability to keep track of what’s at stake in a given decision than we previously thought.

This vast overestimation of how well we can make decisions has unfortunately pervaded the business models of many companies. Whether they’re rolling out a product line, laying out benefits options for prospective employees, or just trying to develop a branding strategy—we continue to embrace more options—even though doing so is about the worst thing we can do.

Choices Are Illusory

Sheena illustrated just how illusory our supposed choices can be by putting a real choice she faced on the screen for the audience. It was between 2 seemingly identical nail polish colors—both given cute names: Adore-a-ball and Ballet Slippers.

The ladies attempting to help her make the choice had all kinds of supposed distinctions by appealing to how “glamorous” one was, compared to the other. Were these women going too far to help her (since Sheena is, in fact, blind)? Perhaps. But nearly half of the women she asked over a period of time accused her of playing a trick on them—and showing them the same color (which she was not).

The point is, there comes a time when there are so many choices that the distinctions between them become nearly non-existent. And in cases like that, we’re back to the Jam Study—where choosers become paralyzed and simply give up without engaging.

We All Want to Be Unique

We can certainly laugh at the thought of millions of consumers agonizing over the choice between 2 seemingly indistinguishable colors of nail polish—but then we miss a valuable point. What paralyzes us in choices like these is an emotional journey that has more to do than picking a product. As Sheena explained: “You see, when we make a choice today, we’re no longer asking ourselves What do I need? Or Which choice will best serve the function that I need to have served?…What we’re asking ourselves is Who Am I?…And if I choose this or that, is it going to send you the right message about who I am and what I want?”

We all want to be unique. And when there are so many choices, it seems like we do, in fact, have a better shot at being as unique as we want to be. And when many of these choices are so similar, we feel so close to finding that fine-grained distinction that Freud discussed in his theory of the narcissism of minor differences. I’m not radically different from that other person, but my subtle differences are what make me (in some way) better or more unique than them.

But in reality, we end up paralyzed by so many choices. Which leaves companies paralyzed as to what to offer and how to offer it to us—so we can actually make a choice.

How To Manage Choice Overload

As choice providers, “how do you enable people to feel empowered by choice? Given all these complexities, how do you prevent people from feeling paralyzed as you try to give them the choices that might make them better able to find the choice that’s the perfect fit for who they are and what they want?”

“I believe that even though people say they want choice, what they really want is to feel competent during the choosing process and confident with the choice that they have made.”

Cut

Less is more has always been true, and is truer today. For example, Aldi is the 3rd largest grocery chain in the world, grew over 15% in 2021, and offers only 1400 products—compared to the average grocery chain’s over 40,000.

As Sheena advised the audience, when she works with retailers on how to streamline their product offerings, she doesn’t bother going to the company’s leadership. Rather, she focuses on asking the Sales Team to provide clear and simple differences between the choices the company provides. Whichever ones can’t be clearly differentiated, are potential cuts.

Concretize

Choices need to be meaningful. For a choice to be meaningful, people need concrete details that can help them almost literally picture how the choice will play out.

Sheena explained how when she worked with ING, she found that when they used AI to generate a picture (a literal picture) of employees at retirement age, they tended to double their retirement savings contribution. When the employees were told to fill out a form detailing what they would do with that money they were saving, participation rates went form 62% – 92%. As if that weren’t enough, their contribution amounts also went up.

Categorize

“The reason why experts are not overloaded by choice is not because they have better memory banks,” Sheena explained. “It’s because they’re able to categorize all the options, and they’re able to dump out the irrelevant options.” The trick, then, is to recreate what helps experts successfully make better choices–but for everyone. That comes down to categorizing.

Sheena insisted that current research indicates we can work with about 25 categories at one time. This is because the question of categories—as opposed to actual choices—is a binary one: “Do I care about this category or not?”

But for categories to be helpful, they have to be meaningfully different. Sheena gave an example of two suggested jewelry categories a company offered: jazz or swing. As you can see, even if you don’t care about either, it’s not clear how they’re meaningfully different. After all, if you care about either one, why wouldn’t you care about the other? They’re much too similar—and not really concrete.

Condition for Complexity

Okay, so if less really is more—and if the proliferation of choices is taking a toll on us (which Sheena was quick to point out—as research shows that an hour of decision-making literally strains our immune systems), why have sales and profits gone up while choices keep proliferating? Well, there is value in customization. There is value in minor differences (though they do have to be meaningful).

Sheena presented a situation where car shoppers were presented with the exact same choices and the exact same quantity of choices: 4 engine choices, 13 steering wheel choices, and 56 exterior color choices. Half the customers started with fewer choices (the engine), and ended with the widest array of choices (the exterior color). For the other half, the order was reversed.

The result? People’s satisfaction with their choices was more when they started with fewer choices, and moved on to more.

As to why this is, Sheen offered up something used in consulting called the 3 x 3 rule. “The idea is to break up complex choices into 3 tiers of 3 choices…My job as a choice provider is not to ask, ‘What do you want?’ You don’t often know what you want. It’s to help you learn what you want. And the way to do that is by tiering the choice so that every step of the way, you understand what the options were, and you understand why you chose what you chose.”

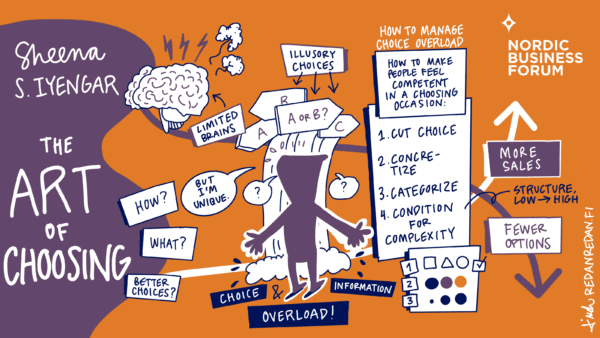

Visual summary of the VIP Session by Linda Saukko-Rauta

Want to get the full summary of the Nordic Business Forum 2023 speeches + extra content for reflecting on your learning? Download your free copy of the full Executive Summary and summaries from previous events!